MASAAKI

NODA

APOLLO'S MIRROR

DEDICATION 26 FEBRUARY 2005

EUROPEAN CULTURAL CENTER

DELPHI, GREECE

Masaaki Noda:

Circumventing “Apollo’s Mirror”

Robert C. Morgan

As I gaze at “Apollo’s Mirror”, a recently installed monumental

stainless steel sculpture by the eminent Japanese-American artist, Masaaki

Noda, I am reminded of a stanza from the famous Greek poet, Cavafy:

Let me stop here. Let me, too, look at nature awhile.

The brilliant blue of the morning sea, of the cloudless sky,

the yellow shore: all lovely,

all bathed in light.*

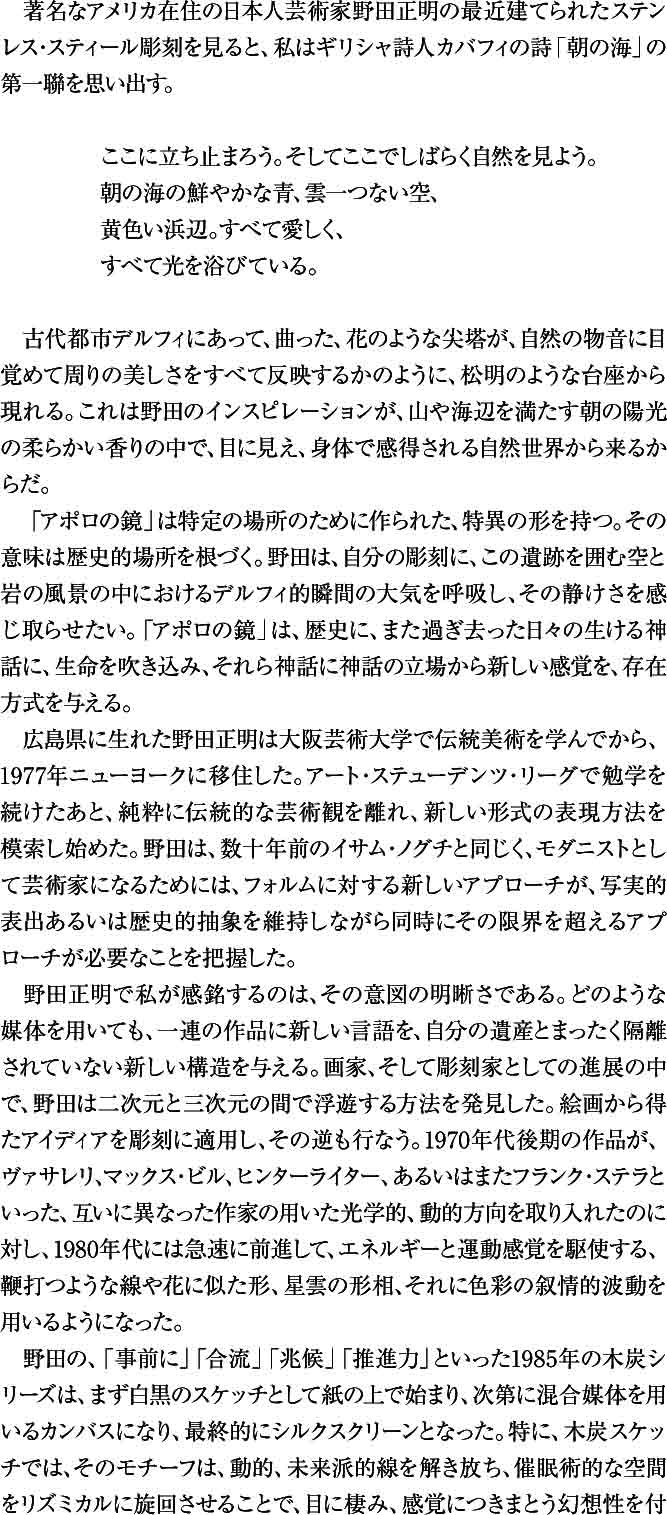

Located in the ancient city of Delphi, the sculpture’s twisting,

floral spires emerge from a torch-like base, as if to awaken the sounds

of nature and reflect all the beauty that surrounds it. For Noda’s

inspiration comes from the natural world of things seen and experienced

in the air or on the ground through the vaporous scent of morning light,

bathing the mountains or the seaside.

“Apollo’s Mirror” is a site-specific, singular form. Its

meaning is embedded in an historic place. Noda wants his sculpture to

breathe the air and to feel the stillness of the Delphic moment in relation

to the sky or the rocky landscape that surrounds the ruins of the past.

“Apollo’s Mirror” is about breathing life into history

and into the living myths of days gone by, and to give these myths a new

sensibility, a manner of being on their own terms.

Born in Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan, Masaaki Noda studied traditional

painting at the Osaka University of Arts before moving to New York City

in 1977. After continuing his studies at the Art Students League, Noda

broke free from the purely conventional notion of art and began to explore

new forms of expression. Like Isamu Noguchi in decades past, Noda understood

that to become an artist in the Modernist sense requires a new approach

to form, an approach that simultaneously retains yet goes beyond the limits

of mimetic representation or historical abstraction.

What I find impressive about Masaaki Noda is the clarity of his intention.

Regardless of the medium, he gives each series of work a special language,

a new kind of structure that is not entirely removed from his heritage.

In his evolution as a painter and sculptor, Noda has discovered a means

whereby he can float between two and three dimensions. Ideas that come

to him through painting may later apply to sculpture, and vice versa.

While his work in the late seventies appropriated an optical/kinetic direction,

borrowing from artists as distinct as Vasarely, Max Bill, Hinterreiter,

or even Frank Stella, he quickly moved forward in the eighties with an

energy and kinesthesia, using whiplash lines and floral forms, constellular

themes, and lyrical cadences of color.

Noda’s black and white charcoal series, such as “Before the

Fact”, “Confluence”, “Indication”, and “Impulse”

(all from 1985) began on paper, first as drawings, then gradually shifting

to mixed media on canvas, and eventually to silkscreen prints. In the

charcoal drawings, especially, Noda’s motif lets loose with dynamic,

futurist lines, circling rhythmically through hypnotic space, suggesting

an infinite vortex of hidden galactic depths, endowed with an illusionism

that inhabits the eye and haunts the senses.

In prints such as “Retrojection” and “Density” (both

dated 1996 - 2003), Noda has articulated a swirling, compact composition

of hyperbolic and parabolic forms moving through a colorful atmospheric

space. “Echo” (2000) and “Foretoken” (2001) also hold

the properties of spatial determinacy, yet shaped more like serpentine

ribbons reminiscent of chromosomes. ?e metaphorical attributes given to

Noda’s precise manipulation of form, pushing and pulling between

micro and macro densities found in the outer limits of time and space

are truly remarkable. As with the Constructivist Gabo, Noda is seeking

the equation between art and science, the metaphor of human identity with

a physical universe that exceeds facile limits or calculations.

Yet Noda’s pictorial images offer only one aspect of time and space.

Another goes into the stratosphere of sculpture, a three-dimensional world

that also includes time, thus emitting an eerie simulation of the physical

universe that surrounds us. In 1995, working with stainless steel, Noda

begin the “Awakening” series in which his twisting parabolic

ribbons emerges from the surface of a welded stainless steel plate, mounted

directly on the wall. Eventually these forms would liberate themselves

entirely from the confines of their metal frames and surfaces.

The beginning of Noda’s luminary sculpture begins in the mid-nineties

as he moves his deftly attenuated ribbons of light -- the “Fluid”

series, for example -- from the wall to the outside world. By 2002, Noda

had established a reputation for his public-scale, outdoor (and indoor)

stainless works on pedestals. ?is is most clearly observed in his “Perpetual

Light” series. His small studies from that year, including “Nexus,”

would eventually become the model for his larger scale work in Delphi,

“Apollo’s Mirror” (2004).

As Noda continued to evolve new and complex forms in sculpture, he was

also developing his kaleidoscopic “Convolution” paintings. While

these pictures retain the futurist dynamism from some of the earlier,

more muted silkscreens, the “Convolutions” (2003)push the space

towards a new kind of surface density. ?e conflicting patterns of the

colorful geometric shapes rarely allow the picture to reach into an illusionist

depth of space. ?e gestural pours and color modulations that intertwine

with these ethereal solids suggests a suspension of illusion rather than

a penetration beyond the frontality of the surface.

It could say that “Apollo’s Mirror” is truly one of Masaaki

Noda’s most comprehensive and culminating works. It is here that

space and illusion come together in a highly articulate and complex way.

?e illusion is not pictorial, but three-dimensional. It takes into account

the environment of Delphi on all levels --geographical, historical, and

mythic. It was here that the name of Apollo, the great poet/warrior, was

proclaimed for all of civilization to know. Illusion is an attribute given

to Narcissus, but it is also hidden within the stoic face of Apollo --

the face that holds steady amid all the Dionysian strife that is hurled

about it. ?e point of reference is unequivocal, and yet, it is in constant

change. “Apollo’s Mirror” moves with the light and alters

how we understand the space on which we stand.

* C.P. Cavafy:Collected Poems (Rev. Ed.), Trans. Edmund Keeley and Philip

Sherrard. Edited by George Savidis. Princeton University Press, 1992,

p. 58.

Robert C. Morgan is an internationally known writer, critic, and curator.

He holds a graduate degree in Sculpture and a doctorate in art history.

He is the author of several books on contemporary art and artists. He

live in New York City where he lectures at the School of Visual Arts and

Pratt